Endurance Sports and Existence

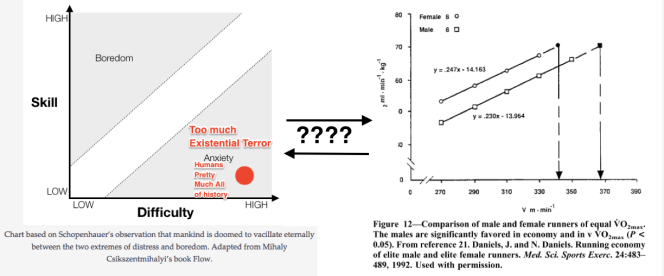

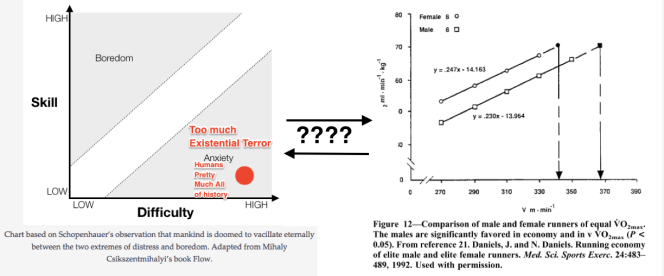

Is is a coincidence that figures describing existential terror and VO2 max look so similar? Maybe not.

The Endurance Sports Part

In endurance sports performance, there are 2 important variables related to aerobic capacity that determine performance; maximal oxygen consumption (VO2 max) and anaerobic/ventilatory/lactate threshold. VO2 max is the maximum amount of oxygen your body can consume during steady-state exercise. What this tells you in more practical terms is the greatest amount of energy your body can provide to your muscles to produce repetitive contractions. This energy to produce muscle contractions is an obvious requirement for movement, so the amount of energy your body can produce is one of the limiting factors in performance. The higher the VO2 max, the higher your theoretical intensity (read=running/biking/swimming speed) will be. But there is another limiting factor that makes this energy level theoretical for endurance performance: threshold.

You may have noticed that I used 3 different terms for threshold: anaerobic, ventilatory, and lactate. These terms are often used interchangeably, and while each specific threshold occurs at roughly the same time, they are not exactly the same thing. Generally speaking, below threshold you have a higher reliance on aerobic, oxygen-dependent metabolism, and above threshold you have a higher reliance on anaerobic metabolism. The specific differences between each type of threshold are not relevant to my larger point in this article, so if you’re interested I can get into that later. For now, I’ll just use “threshold” as a generic term.

While VO2 max is the limiting factor for energy production, threshold is what really sets the limit on performance. During endurance events (metabolically this is anything longer than ~3 minutes) our bodies rely heavily on aerobic metabolism. There are several reasons for this: exercise intensity, muscle fiber type, rate of energy usage, and availability of energy sources (blood glucose, free fatty acids, muscle glycogen and fat stores). Working at a level below threshold means your body is able to meet the metabolic demands of the exercise intensity while still relying mostly on aerobic metabolism, therefore allowing you to maintain the intensity. The higher your threshold as a percentage of VO2 max, the greater intensity (i.e., speed) you will be able to maintain. This why VO2 max is the theoretical maximal intensity, no one runs a marathon at max (I dare you to try) because threshold is what will truly determine your intensity during prolonged exercise.

While VO2 max and threshold are different things, they are not mutually exclusive. Generally, you can train to improve one and the other will be affected. Results may vary a bit based on fitness level and training mode; for the least fit doing ANYTHING helps EVERYTHING, when you’re already high level you have to be a little more specific. You don’t need to be an exercise scientist to know this though, the better shape you’re in the harder you have to work and if you’ve ever trained to improve performance you’ve experienced this. If you want to learn more about these concepts I highly recommend a review article by Basset, et al. which explains concepts related to performance quite eloquently, and is where that VO2 max figure came from.

Now that I’ve (somewhat) explained the science of thresholds in endurance sports, I can get to what I really wanted to talk about; existential max and threshold.

The Existence Part

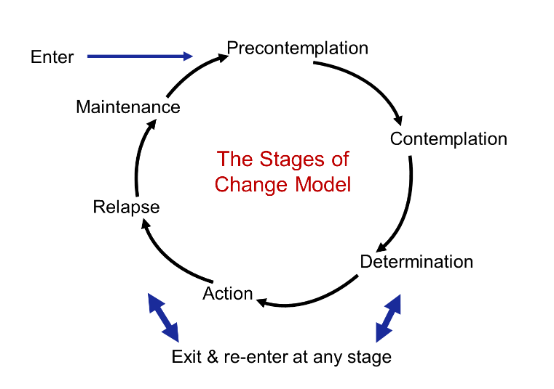

I constantly find parallels between endurance sports training/racing and life. I like the physical challenge of long races, I like seeing how far I can push myself, and of course I like to get on the podium. Anyone who has properly prepared for a long race knows that the big deal is not really the race, it’s the weeks, months, or years spent training for it. It’s this part of it that keeps me coming back for more. I find that the time I spend training is when I really learn about myself. Maybe it’s all the hours I spend alone with my thoughts, maybe it’s the endorphins circulating in my brain, maybe it’s the pain tolerance I’ve had to develop to be able actually DO the training and racing. Maybe it’s all of them. Either way, the idea that the more you push yourself, the more you will be able to withstand has been presenting itself in more than just my training.

Most recently I’ve seen it in my academic career. I recently completed the second biggest step in my PhD, the comprehensive exam. I’ll spare you the mundane details of the test, but it takes about 3 months to complete the whole process and it’s extremely high pressure, high stress, and high consequences. If you don’t pass comps you have an opportunity to retake it, but if you don’t pass on the second go, you basically get kicked out. It sounds like the kind of thing that would make you lose sleep at night, and I can’t say that I wasn’t very stressed out during the process, but it wasn’t as bad as you’d think. How is this possible?

I think it’s because during winter/spring semester 2017 (WS 2017) I had the absolute worst 5 months. I took a 4-week winter class on my LEAST FAVORITE topic (Matlab programming) that led straight into a grueling semester that was loaded up with challenging classes. That semester I found a new level of discipline that got me up around 6 on most mornings, and from the first week of January to the end of the semester in May I worked every single day (including weekends) except for 5 days in March when I took a short spring break trip. The semester didn’t end that well and I was in a pretty deep hole mentally that took me until August to crawl out of. I can’t imagine having to go through a time like that again (please, please, no) but the benefit is that I’m so much better equipped to deal with insane workloads and the associated stress. That semester increased my workload and stress max for sure.

While WS 2017 increased my max, I think comps increased my threshold. The stress was intense, but I knew it was for a finite amount of time and once it was all done things would improve dramatically. Since comps wasn’t the worst academic situation I had been in I handled it much better, and sometimes I was even afraid people would think I wasn’t taking it seriously enough because I was not excessively stressed out about it-just normally stressed out, if that’s a thing. Things that seemed overwhelming before are now at least doable, and things that used to stress me out a lot are just business as usual. My threshold for what is academically difficult has been gradually increasing over the years, but comps really pushed me to a new level.

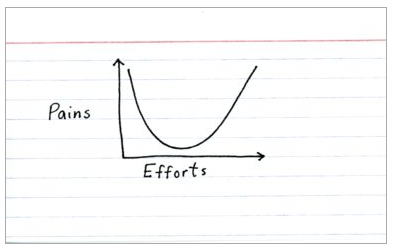

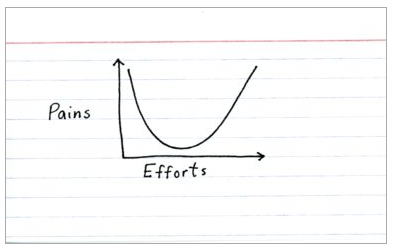

Jessica Hagy draws it best.

Jessica Hagy draws it best.

If you want to increase your threshold by training, you have to do some truly grueling workouts. These workouts usually involve gasping for air, burning muscles, and lots of fatigue and pain (of the best kind, of course). The intensity is hard to maintain, hard to push through, and it takes a lot of determination not to give up in the middle. I usually dread these workouts, although I do feel extremely accomplished once they’re over. This also describes how I feel about the academic threshold I’ve finally reached. School has been grueling, painful, discouraging, and challenged me in ways that I never imagined it would or could. Finally though, I’m starting to feel that this process has made me smarter, stronger, and more capable.

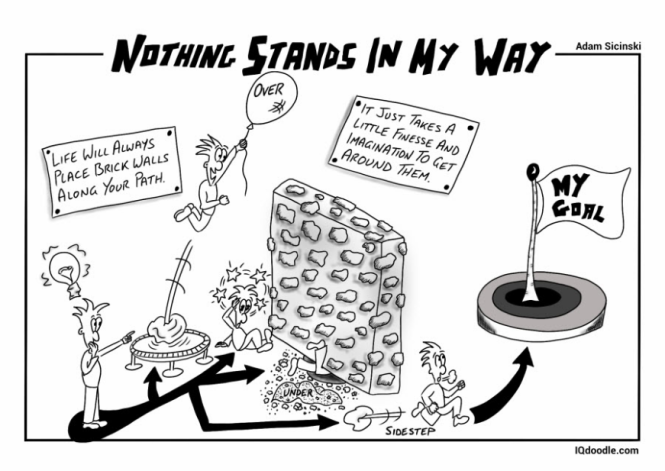

Just like during the hardest workouts and the longest races, there have been so many times I wanted to quit. During these times I’ve asked myself: Why am I doing this to myself? What is the point of all this? Is it really necessary for me to suffer like this especially when it is all self-inflicted? My own rebuttals to these questions are what have kept me going. I’ll be stronger or smarter if I push through. The point is to become a better person. What is the long-term benefit you can focus on instead of the acute discomfort? How will you feel about yourself if you quit now?

If you want to increase your threshold it does not mean you have to kill yourself with a crazy training program or go get a PhD, but you DO have to get out of your comfort zone. Building up endurance and tolerance can and should be a gradual process, otherwise you’re likely to burn out or get overtrained, neither of which are productive. Start with small challenges and work your way up. The point is, the more you push yourself the further you are able to go. You may find that you are capable of things you never imagined, existential crisis not required.

Credit for this cartoon is from here.

Credit for this cartoon is from here.

While I’m buried under 2 feet of snow by winter storm Jonas, I’m dreaming of the days when I lived in Miami and got to complain about how anything under 70 was cold. I’m also really missing my outdoor pool where I swam year round, even on those frigid 60-something degree days! I haven’t done any triathlons or serious triathlon training since I moved north in August and I’m seriously missing it. Considering the work I’ll have cut out for me to get back into the training routine, I’m most concerned about the swim. It’s my weakest event already and even though I’m still swimming here and there, nothing compares to the hard training I was doing even a year ago. The swim is the smallest portion of the entire race which is good for me, but I think the importance of swim performance is often downplayed. Yes, I can still perform very well overall although I am very middle-of-the-pack on the swim, but think about how much better I’d do if I was even in the top 25%! Lots of studies measured how cycling affects running, but not as much attention is paid to swimming.

While I’m buried under 2 feet of snow by winter storm Jonas, I’m dreaming of the days when I lived in Miami and got to complain about how anything under 70 was cold. I’m also really missing my outdoor pool where I swam year round, even on those frigid 60-something degree days! I haven’t done any triathlons or serious triathlon training since I moved north in August and I’m seriously missing it. Considering the work I’ll have cut out for me to get back into the training routine, I’m most concerned about the swim. It’s my weakest event already and even though I’m still swimming here and there, nothing compares to the hard training I was doing even a year ago. The swim is the smallest portion of the entire race which is good for me, but I think the importance of swim performance is often downplayed. Yes, I can still perform very well overall although I am very middle-of-the-pack on the swim, but think about how much better I’d do if I was even in the top 25%! Lots of studies measured how cycling affects running, but not as much attention is paid to swimming.